Every five years, the United States has the task of renewing its omnibus farm bill. The current legislation, the Agricultural Act of 2014, expires in September 2018, and new drafts are already being debated. The bill is designed to support farmers and the food community, based on the U.S. needs for nutrition, crop insurance, conservation and other commodity programs.

So what influence does a major crop like corn — the United States' most dominant in terms of acreage — and its farmers play in shaping the next farm bill? A lot.

Advertisement

In 2016, for instance, U.S. corn farmers yielded a total of 86.7 million acres (35.1 million hectares) of corn. This crop was valued at $51.5 billion, far exceeding the $40 billion value of America's second largest food crop: soybeans.

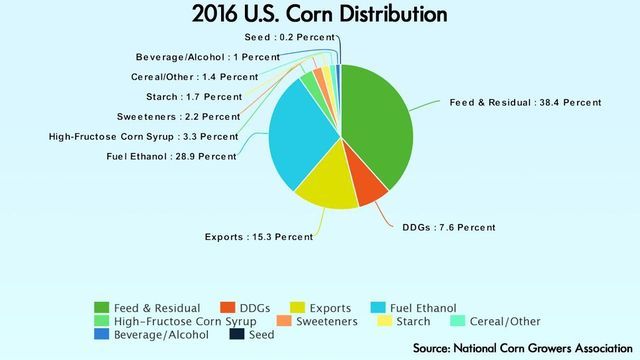

Where does this corn go? The answer might surprise you. Just 205 million bushels (or 1.4 percent) of the 15.1 billion bushels produced in 2016 went to cereal and other foods. (An average bushel of corn weighs about 56 pounds.) Another 480 million bushels (3.3 percent) went to make high-fructose corn syrup, a sweetener used by the food industry. And a large percentage — 15 percent — or 2.2 billion bushels was exported.

Much of the rest goes to feed livestock (5.6 billion bushels, 46 percent) or to produce ethanol (4.2 billion bushels, 28.9 percent). In fact, corn is the most widely produced feed grain in the United States.

What these statistics mean is the U.S. devotes more than 90 million acres (36.4 million hectares) of farmland to corn, but very little of that is grown for human consumption. "People need to stop thinking about corn as food," says Mark Lambert, senior communication director at the National Corn Growers Association. "It's very versatile. It's not just food. We're growing way, way more than what we need for food purposes because we can."

But does "because we can" mean we should? The answer is complex and multifaceted. First, the Agricultural Act of 2014 includes several different farm subsidies and types of crop insurance, which could have influenced why the U.S. grows so much corn. Before the late 1990s, crop insurance was designed to assist farmers when crop yields fell short from disasters like weather.

However, according to Colin O'Neil, agriculture policy director at Environmental Working Group, these subsidy programs now pay out regardless of crop yields. They're subsidizing revenue instead. Take 2016, for example. Corn growers had a record year; remember, 86 million acres (35.1 million hectares) of corn was harvested worth $51.5 billion. But many farmers were still able to collect subsidy payments because the 2016 harvest price for corn was set at $3.49 per bushel, 10 percent lower than the $3.86 projected price.

So why the shortfall in corn prices in 2016? Perhaps it was due to simple supply and demand. Take 2016 again: It was the third-largest corn crop haul planted in the U.S. since 1944. So with such a strong demand and large supply, the price per bushel went down, leaving taxpayers to pick up the difference via subsidy payments.

And whether the U.S. should grow so much corn is not just a question of economics; it's also a question of good environmental policy. In 2014, for example, the U.S. government's National Climate Assessment research program reported that climate change could significantly impact the Midwest and the Great Plains in the coming years, decreasing yields and driving prices higher. The reason is simple: Corn is a thirsty crop that can be easily impacted by extreme drought, devastating heat waves and the lack of precipitation. Crop yields decline when temperatures get hotter and rainfall is limited.

Corn also consumes a large amount of freshwater, roughly 5.6 cubic miles per year — that's about 6.1 trillion gallons (about 23 trillion liters). That water comes from lakes, rivers, streams and underground aquifers. Heavy rain can delay planting and decrease production.

Runoff from these farmlands is also another environmental concern. Corn uses more fertilizer than other crops, about 5.6 million tons (5 metric tons) of nitrogen fertilizer each year. As a result, the chemicals and soil wash into waterways when it rains, polluting rivers, streams and oceans. The results can be seen in the Gulf of Mexico where scientists say excessive nutrient pollution has created a hypoxic, or low-oxygen, dead zone for aquatic life at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

And all that corn that the U.S. turns into clean-burning ethanol? Environmentalists say ethanol production isn't efficient. Growing and processing corn into biofuel uses a huge amount of land and fossil fuel, which ultimately negates any environmental benefits.

Some think the way to fix the problem is to craft a farm bill that would prioritize farming of healthier foods that are grown in more environmentally friendly ways. Jonathan Foley, executive director of the California Academy of Sciences, wrote: "This reimagined agricultural system would be a more diverse landscape, weaving corn together with many kinds of grains, oil crops, fruits, vegetables, grazing lands and prairies. Production practices would blend the best of conventional, conservation, biotech and organic farming. Subsidies would be aimed at rewarding farmers for producing more healthy, nutritious food while preserving rich soil, clean water and thriving landscapes for future generations. This system would feed more people, employ more farmers, and be more sustainable and more resilient than anything we have today."

Advertisement