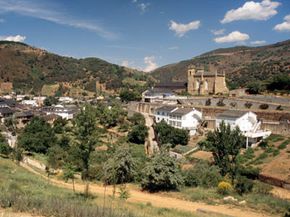

In the north of Spain, in Castilla y Léon, is the often-overlooked region of Bierzo. Rural, rustic and inaccessible, without the urban bustle of Madrid and Seville or the sweeping architecture of Barcelona, Bierzo was left to itself for much of the last millennium. That's one of the reasons you may be unfamiliar with the area up until now. Recent years have brought new attention to the region and its wine.

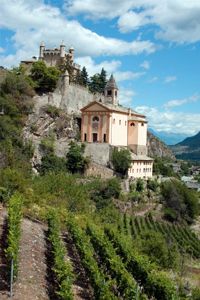

Bierzo has been gaining increasing attention since it first received official recognition as a DO (Denominación Origen, which is similar to France's AOC and Italy's DOC) in 1989 [source: Apstein]. The man widely recognized for the area's resurgence is Alvaro Palacios, who, with his nephew Ricardo Pérez, began growing grapes here in the 1990s [source: Schoenfeld].

Advertisement

Bierzo's renaissance is as homespun and handmade as they come. Vineyards are generally tiny here, devoted exclusively to native species, and many of Bierzo's wines are single-vineyard products. Some vineyards, in fact, produce fewer than 1,000 bottles a year [source: Schoenfeld]. That scarcity is likely to drive up the price of these Spanish wines as Bierzo attracts more and more attention. Fortunately, Bierzo's dark, expansive wines -- some of them not even oaked -- tend to age well, so you can buy a bottle as an investment when it's young. With trends leaning toward quality over quantity in recent history, Beirzo's small numbers may not hold them back.