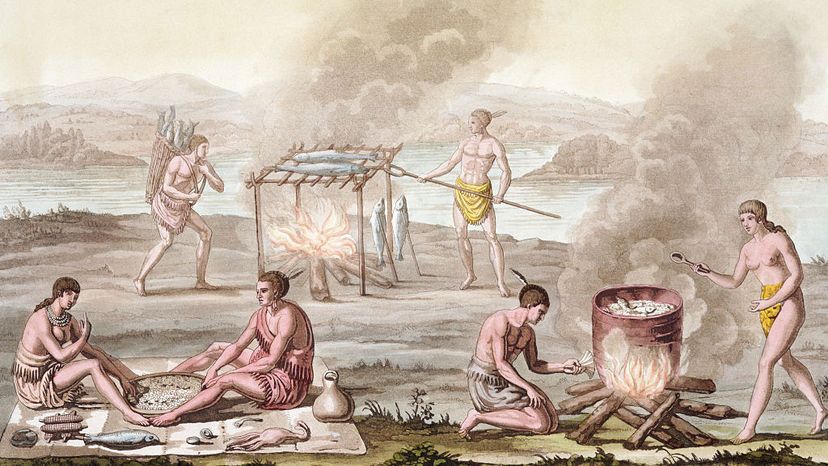

Barbecue is one of the most beloved of American traditions. From Fourth of July picnics to the joints that became gathering places in towns and cities, barbecue has brought people together to socialize, raise money for important causes, decide which political candidates to support and just enjoy some good eating. Beyond that, barbecue has helped reinforce the American ideal of egalitarianism. It's a cuisine that is beloved by the rich and poor, by whites and African-Americans alike.

Some people use the word barbecue as a verb, others as a noun and a verb. In the strict sense, barbecue is the art of preparing and cooking meat slowly over burning wood that gives off smoke to add to the flavor, and then serving this meat with a sweet or spicy sauce [source: Moss].

Advertisement

But barbecue is much more a type of cooking. It's a ritual that over the past five centuries has become an intrinsic part of American life, particularly in the South, but also in the Southwest and Midwest. George Washington famously enjoyed barbecues, and Abraham Lincoln's parents held a barbecue after their wedding in 1806 [source: Raichlen].

"To trace the story of barbecue is to trace the very thread of American history," barbecue historian Robert Moss has written.

No kidding. Americans are so passionate about barbecue that the subject has inspired a whole literary genre of barbecue books — not just collections of recipes, either, but histories and meditations on its cultural meaning. Musicians have composed scores of songs about the cooking style, ranging from Louis Armstrong's 1927 tune "Struttin' With Some Barbecue" to ZZ Top's 1972 cut "Bar-B-Q" [source: Drozdowski].

One reason for Americans' enduring devotion to barbecue may be its complexity. Barbecue is the antithesis of fast food. It takes many hours of careful preparation and slow, deliberate cooking to produce a plate full of tasty ribs or a pulled-pork sandwich. And the details — from what woods to use for smoke, to the cuts of meats, to the subtle chemistry of the sauce that a pitmaster (a person who's mastered the art of barbecue) uses — all vary from region to region and pitmaster to pitmaster. Barbecue aficionados engage in endless spirited debates about which techniques, food spots and pitmasters are the best.

In this article, we'll look at the history of barbecue, and the regional and international styles that have developed over the centuries. We'll also discuss barbecue's important place in American politics and racial issues, and pay homage to some of the cooking style's most influential pitmasters.

Advertisement