Good wine is one of life's greatest pleasures. Whether you are a novice or a connoisseur, interested in simply sipping or expertly analyzing, enjoying a glass of wine can be a sublime experience.

Unfortunately, many people find wine and how to choose, serve, and describe it more intimidating than enjoyable. The very scope of the topic seems daunting. But never fear -- you don't have to take a class to appreciate the subtleties of fine wine.

Advertisement

Still, as with many things in life, a little knowledge goes a long way. Just as a musical performance is enhanced by knowledge of the composer or the piece, a bottle of wine is more enjoyable if you know something about it. Learn to taste the story in the wine, and you can transcend the intimidation.

To appreciate wine as something more than mere drink, all you'll need is conscious, deliberate awareness. Let's face it: It makes little sense to pay the premium for wines of character only to swallow them unconsciously. Each wine has a personality waiting to be discovered: You just need to decide whether you like it.

This is a very personal endeavor. Responses to wine are as individual as fingerprints. An aroma or flavor that is pleasing to you may not be so to another. The trick is translating your preferences into words. Accomplish this, and you will add new dimensions to your enjoyment of wine.

So, how to begin? You begin by understanding what's in your glass, tasting what's in your glass, and evaluating what's in your glass. Sampling wine and recording your impressions is an effective (and festive!) way to gain confidence choosing and evaluating wine. In this article, you will learn about all the aspects of wine and wine tasting. You will learn about the various varieties of wine and how they are made, as well as how to taste and appreciate wine.

In many ways, beginning a quest for wine knowledge is like entering a whole new world: a new language to learn, new techniques to master, and so many wonderful selections of wine to sample. Enjoy the journey!

Getting Started

As you set out to explore the world of wine, you might feel unsure about how to begin. Should you take a class? Join a wine-tasting group? Visit a winery? Buy a variety of wines and start sampling? There's not one set rule you must follow; rather, think of it as having unlimited choices! The following tips may help you find your way:

Find a guide. Every new journey benefits from the presence of an experienced guide. Whether you're exploring a mountain landscape, the wildlife of a faraway land, or the ins and outs of wine, an experienced guide can be your key to discovering hidden gems and expanding the horizons of your knowledge. You might try your local wine merchant, a wine-bar operator, a knowledgeable bartender, a wine educator, or even a friend who knows more about wine than you do.

Hit the books. This might seem like an obvious step, the wealth of available information can be a little overwhelming to even the most eager wine connoisseur. With books, magazines, newsletters, and Web sites offering opinions, evaluations, criticisms, and historical perspectives on everything from winemakers and vineyards to wineries and growing regions, you should have no trouble establishing a foundation for learning.

Learn the language. Consider subscribing to a wine magazine (or two or three). Filled with pages of wine reviews, a good wine magazine offers a leisurely opportunity to learn the language of wine. Merchants' newsletters and offering catalogs are also good sources for building a wine vocabulary and learning about particular styles of wine and growing regions. What's more, these sales materials are usually mailed out free of charge, so arrange to receive several, including those from merchants beyond your hometown. By developing a rich wine vocabulary early on, you'll find it easier to express your impressions and preferences.

Taste as often as opportunity allows. This is the enjoyable part! There's no substitute for tasting, tasting, and more tasting. Try more than one wine at a time for the sake of comparison. Add a few friends to the mix for a truly festive time!

Treat yourself to good wine. The most vivid and memorable attributes of a varietal (a wine made from a specific grape variety, such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Chardonnay), a growing region, or a vintage are most easily discovered in wines of high quality. So, taste the best you can afford. That way, you'll get a more distinctive palate (or taste) memory. Occasionally splurge on a truly great wine: It's an excellent way to reward yourself!

Experiment with the unfamiliar. Life is too short to restrict yourself to the "vanilla" and "chocolate" of the wine world: Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon. Take advantage of an opportunity to taste a wine you've never heard of. You may decide you don't like it, or it may prove delightful, opening up an entirely new avenue of wine exploration. Either way, you've added another dimension to your wine adventures.

Express yourself. It's difficult to know how or where to start describing a wine. And though it seems easy enough to sip and swirl the wine to judge its flavors, this can be a fleeting experience, one that may not add much to your taste memory in the long run. For this reason, it's a good idea to take some brief notes while you are sampling a wine, even if you never look at them again. The act of translating your instincts into words challenges you to make judgments and resolve uncertainties.

Enjoy yourself. Learning about wine should never be frustrating. After all, the goal here is to increase your enjoyment of wine.

Be patient. No one becomes an authority in a day, a week, or even a month. Knowledge comes with experience, and experience is only gained with time and patience. And there's always something new under the sun, even for the experts. Fortunately, the journey is as sweet as the destination.

Whatever you seek to learn, which wine to serve with dinner, the differences between Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris, how to read a wine label, techniques for wine tasting, the first step of your journey starts here.

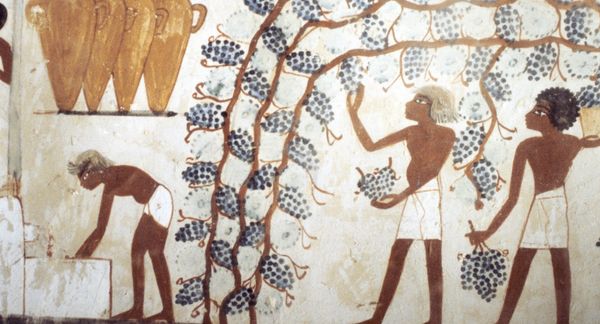

It's All About the Grapes

If you've ever glanced at a restaurant wine list or browsed the wine aisle of the grocery store, you know there are a lot of different kinds of wine out there. But that's just the tip of the iceberg. Several hundred grape varieties are used to make the world's wines, resulting in different flavors, personalities, and qualities. The sheer variety can make choosing just one bottle a bit overwhelming, especially when they all look so enticing. Then again, isn't it fun to consider the possibilities?

Although many kinds of grapes are used to make wine, only a fraction (the classic or noble grape varieties) produce truly superior wines. For red wine, noble grape varieties include Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, and Syrah; for white, Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc, Riesling, and Sauvignon Blanc. Other noteworthy though less extraordinary grape varieties include such reds as Cabernet Franc, Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, Tempranillo, and Zinfandel; and such whites as Gewurztraminer, various types of Muscat, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Semillon, and Viognier.

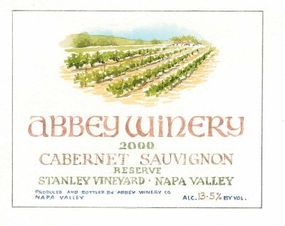

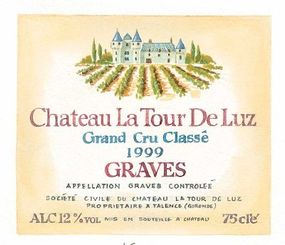

A varietal wine is made primarily or exclusively from one grape variety. The minimum required percentage of the named grape is regulated by law and differs from country to country (or from state to state in the United States). California law, for example, requires that a varietal wine contain at least 75 percent of the grape named on the label. So a California Merlot must be at least 75 percent Merlot grapes, and a California Chardonnay must be at least 75 percent Chardonnay grapes.

In the "New World," essentially the United States, South America, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, most wines are named for the grapes from which they are produced. However, wines from "Old World" countries like France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain are usually named for the region in which the grapes were produced. So, a California wine made from Chardonnay grapes is labeled Chardonnay, but a French wine made from Chardonnay grapes might be called Chablis or Mersault (among other names), depending on the growing area.

If you are relatively new to the world of wine, it's best to explore the principal varietal wines first. Because these wines have a stronger flavor "personality" than those of lesser, more obscure varietals, they're more likely to make a lasting impression on your palate.

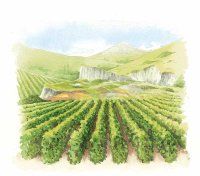

As you taste, keep in mind that wine grapes are products of the soil and climate of the vineyard in which they are grown; the same grapes can produce two wines that taste completely different; it all depends on where each vineyard is located. Viticulture practices (the way the vines are tended and how much fruit they are allowed to produce), the vines' age, the winemaker's skill and philosophy, and winery equipment also enter into the equation.

There are a lot of different wines out there to taste, and keeping them straight in your head can be difficult. In the next few sections we will explain the different varieties of wine in terms of taste and where in the world the grapes are grown. We'll begin on the next page with white wines.

Advertisement