War is hell — and sometimes the coffee is, too.

Consider the American Civil War, a four-year bloodbath that divided a nation and claimed the lives of between 650,000 and 850,000 Union and Confederate soldiers. Looking back at such dark times, there's solace to be found in moments of humanity, be it sweeping acts of moral responsibility or small fragments of everyday life sprinkled amongst the madness, like complaining about wretched coffee.

Advertisement

Food industrialization has always progressed alongside modern warfare. An army, as the saying goes, marches on its stomach, so the streamlined production, preservation and delivery of food offer a definitive military advantage.

Evaporated milk is a fantastic example of a successful industrialized food product. It's essentially just milk dried into a paste and, in the process, pasteurized. All you have to do is add water and, behold, you've got yourself some reconstituted milk. (Condensed milk is roughly the same idea, only with a whole lot more sugar added.) It's not perfect, but it gets the job done, which is why the U.S. government purchased a lot of condensed milk for Union Army field rations.

But great ideas often lead to terrible ones— in this case, the Essence of Coffee. Food engineers wondered, "Hey, if we can successfully evaporate a glass of milk, then why not an entire cup of coffee?"

This was no trivial matter. The Union Army thrived on coffee, as Jon Grinspan explained in his New York Times article "How Coffee Fueled the Civil War." It was their "nerve tonic" and sustainer. Gen. Benjamin Butler even considered it a decisive strategic factor, notes Grinspan. The modernization of coffee was nothing short of the modernization of the war effort itself.

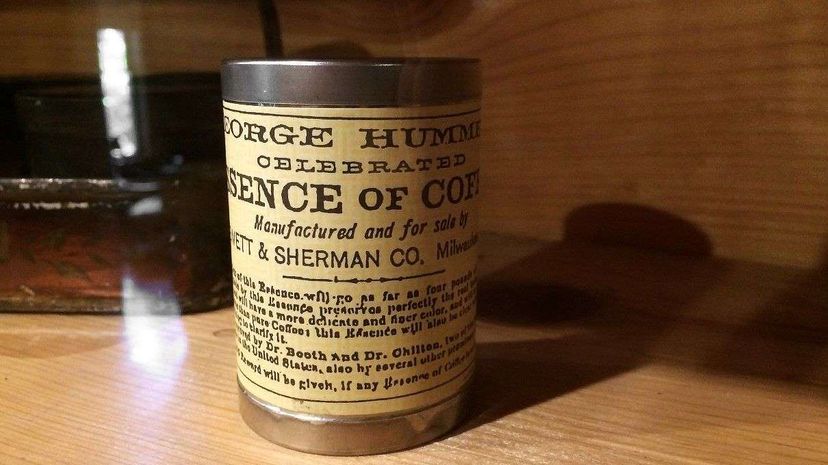

And so George Hummel unleashed the Essence of Coffee on an unsuspecting world, evaporating vast quantities of coffee — complete with Borden's condensed milk and sugar — into what is often described as a thick, brown sludge or a noxious, black grease. By all accounts, Union soldiers abhorred the stuff, and these were men who, according to Grinspan, would brew coffee with water from "brackish bays and Mississippi mud, liquid their horses would not drink" if that's what it took to sharpen their nerves and minds on the whetstone of holy caffeine.

Despite the label's insistence that the product was "celebrated" and "more wholesome than pure coffee," the Essence of Coffee tested even the standards of these hardened soldiers. If that weren't bad enough, the men's already super-charged bowels were sometimes further corrupted by spoiled milk sold by sketchy dairymen, according to writer David A. Norris. So attempts to cut the reconstituted essence with "fresh" milk could prove a risky gamble.

The Essence of Coffee was soon removed as a ration, but its reputation lingered, according to John D. Wright, author of "The Language of the Civil War." In recent years, a few determined (and potentially masochistic) Civil War re-enactors have attempted to recreate the stuff with mixed results. While some claim to have improved on the recipe and concocted something "really quite good," others report the creation of a tough taffy that must be broken up with a rifle butt on cold days before boiling.

Can anything good be said for the Essence of Coffee? According to historian James T. Hickey, first lady Mary Todd Lincoln may have incorporated the stuff into a high-caffeine, molasses-sweetened concoction to treat her frequent migraines. Plus, Union soldiers who could stomach the stuff undoubtedly got their fix, a jolt of psychoactive stimulation that helped push them toward victory in the War Between the States.

So think about that the next time your barista serves you a less-than-perfect pumpkin spice soy latte. At least you're not forced to endure "the essence."

Advertisement